Two years ago, my dad got sick. He was 92 and, with the exception of some childhood bouts of pneumonia – the result of growing up in a house full of chain-smoking coal miners – he’d been robustly healthy his entire life. That he survived the twin assaults of Valley Fever and pneumonia was surprising. That today, approaching 95, he still takes ballroom dance lessons, requires not a single medication, and reads the New York Times, amazes me.

My father was an ice dancer until he was 80. Then he took up ballroom, which, despite the illness that almost killed him, he still enjoys today.

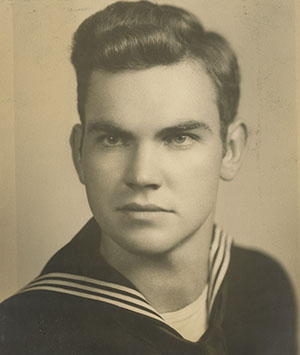

However, my dad is not the same as he was before his illness. His mind was altered, leaving him fuzzy in the short-term memory department. Ironically, and like many elderly people, he has no trouble recalling in vivid detail events that occurred many decades ago. The Japanese kamikaze that flew so close to his destroyer escort he could see the young pilot’s eyes before the plane narrowly missed the ship and plunged into the sea. The sailor plucked from dark, oil-slicked water who lay in his arms and asked for a cigarette before dying. The shipmate who worked as Mickey Rooney’s stunt double who sometimes climbed the mast and performed swan dives into the ocean. And the bodies of downed pilots, in a neat row on the deck, tarp covered save for their feet which rocked rhythmically as the ship swayed beneath the night sky, waiting to be buried at sea.

My father served on a destroyer escort during World War II. The men of the USS Ulvert Moore fought in numerous battles, including Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Bright and clear is another memory my dad carries, one of a ten-year-old growing up in the mining town of North Irwin, Pennsylvania. The small dwelling on Penn Avenue housed immigrants, Irish in my father’s case. But Italians, and Poles, and Russians, and others lived on the street, as well, all sharing something in common. They were poor.

“Dad’s taking you to a ballgame,” his mother called.

Clad in knickers with clasps below the knees, brown shoes and socks, and a white button-down, my father balked when she handed him a sack lunch bearing a chicken sandwich and a small red apple.

“I wanna get lunch when I get there,” he said. “Everyone buys their lunch at the ballgame.”

My grandfather – thin, balding, blue eyes dancing beneath the brim of a fedora – smiled, then ushered my dad to the train station. There was no money to make the trip to Pittsburg’s Forbes Field, but my grandfather worked for the railroad – one of the few members of the the Butler clan to avoid laboring in the mines – so they rode the train for free.

My dad still clutched his sack lunch on the street car that would drop them in front of the stadium.

“I wanted to hide it,” he said. “I put it under the seat because I didn’t want people to see it.”

After disembarking at Forbes Field, they were caught in an excited wave of baseball fans rushing to get into the game. When they settled into their seats, my dad tucked the brown bag out of sight.

The game got underway, but then a strange murmuring swept through the crowd. My dad turned and, up in the stands on the third-base side, he saw a couple approaching.

“The man was young, dashing. Black hair. Big smile. Well dressed. She was a beautiful lady. Blonde. She looked like a movie star. People were waving at them.”

And there was something else.

“He was carrying a two-handled picnic basket.”

“What are you looking at?” my grandfather asked. “I think there’s gonna be a squeeze play.”

But my dad kept staring at the couple.

“Paul, you have to watch the game. Is there something wrong?” My grandfather turned.

“I don’t understand why anyone would bring a picnic basket to a ballgame unless they were real poor. He doesn’t look poor.”

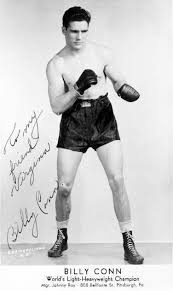

“Paul, he isn’t poor!” my grandfather said. “That’s Billy Conn, the Light Heavyweight Champion of the World.”

Conn, an Irish-American boxer and local favorite called The Pittsburgh Kid, was known for being cocky and brash, his fights against Joe Louis, and his 63-11-1 record.

My dad continued to keep his brown bag hidden beneath the seat as he watched the game that day, taking a bite occasionally, hoping no one would notice. He wondered about the glamorous couple, sneaking peeks as they snacked on their picnic-basket lunch. He thought about what it meant to be poor.

A chance sighting of world champion boxer Billy Conn had my then ten-year-old father pondering what it meant to be poor.

“I should have been proud to be able to go to the ballgame,” my dad said, blinking blue eyes that look just like mine. “I learned that I shouldn’t worry about what other people might think of me.”

I thought about his wise words, a lesson he learned at the tender age of ten, a time he still recalls so vividly.

Thanks to the G.I. Bill, my father would earn a bachelor’s degree from Penn State University. When I was eight, I watched from the balcony as he received a master’s degree from Seton Hall. Because of his stint in the Navy and his education, we were never poor, something that, as a ten-year-old, he might have been comforted to know.

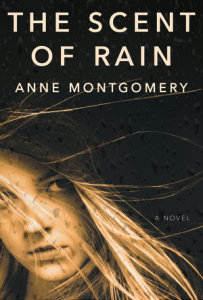

Anne Montgomery’s novel, The Scent of Rain, tells the story of two Arizona teenagers whose fates become intertwined. Rose flees into the mountains to escape from her abusive polygamous community where her only future is marriage to a man older than her father. Adan, whose only wish is to be reunited with his mother, is on the run from the cruelties of the foster care system. Are there any adults they can trust? Can they even trust each other? The Scent of Rain is available at https://www.indiebound.org/book/9780996390149 and wherever books are sold.

Wonderful post, Anne. So lucky to still have your father. I miss mine everyday. Hugs and happy holidays to you and your family! Cheers!

LikeLike

Thank you, Sharon. The surprising thing is that I’m now hearing stories he never told before. Happy holidays back at ya’.

LikeLike

Wonderful story to share at Christmas!

LikeLike

Thank you, Chris. 🙂

LikeLike