This almost 400-year-old plantation site on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands is home to a laboratory designed to cultivate coral and return it to the sea, an effort to help restore our Caribbean coral reefs.

The sign on the dirt road read “Estate Little Princess Established 1738”. The 25-acre plot which lies just west of Christiansted on the St. Croix coast was once a sugar plantation. You can still see the tall sugar mill—one of about 100 that dot the island—a testament to the liquid treasure of the rum industry, wealth made on the backs of the almost 29,000 African slaves that were transported to what are today the U.S. Virgin Islands during the Danish Colonial Period.

The beauty of the place is overwhelming with its flashy green flora and scarlet Flamboyant trees. Not that the most important residents would notice. The tiny corals that reside in special protected tanks lie placidly, waiting for their chance to be released into the sea.

“You see this?” Our guide, Semoya Phillips of the Virgin Islands Coral Innovation Hub, pointed at a large chunk of coral partway up the side of the property’s sugar mill. “It was gouged out of the reef because building material was needed. The people believed it was a renewable resource.”

And while coral does grow back, the process is painstakingly slow. That’s why the Nature Conservancy helps fund the lab facility. Here’s how they explain it on their website: “The Nature Conservancy and partners are advancing coral science to help reefs recover at a meaningful scale. Using our land-based and underwater nurseries, we are innovating ways to breed significantly more corals, with greater survival rates, for reef restoration. Novel techniques allow us to dramatically increase coral growth and preserve coral genetic diversity for improved reef resilience. Healthy new corals are then used to bring dying reefs back to life and restore the benefits they provide for our ocean, communities and economies.”

Some of you may be thinking, “Gosh! Why should I care about coral reefs?”

Here’s the thing. Do you like to breathe? Note that our oceans produce 50% of the oxygen in our atmosphere. And coral reefs do their part because they house algae called zooxanthellae that convert carbon dioxide and water into energy through photosynthesis and—bada bing bada boom—release oxygen into the atmosphere.

And there’s more! When those big bad hurricanes come roaring ashore, it’s coral reefs that slow the water down, lessening the damage from storm surge. Twenty-five percent of the world’s fish grow up in the protective nooks and crannies of coral reefs before venturing out to sea—think Finding Nemo—with over 4,000 species dependent on coral reefs at some point in their fishy lives. So, with about 500 million people dependent on fish for food, the decimation of coral reefs could cause worldwide starvation. And let’s not forget the benefits of ecotourism. In the interest of full transparency, I’m a scuba diver and can think of nothing more delightful than floating above a shimmering reef watching jewel-colored fishes dancing in the sunlight.

So, yes, we need to do all we can to save our reefs, which are dying off at unprecedented rates due to warming seas cause by climate change. The rising temperatures force the corals to expell the algea that give them their beautiful colors, bleaching that often leads to the death of the colony. Pollution, over fishing, and costal development, among other things, are also destoying the reefs.

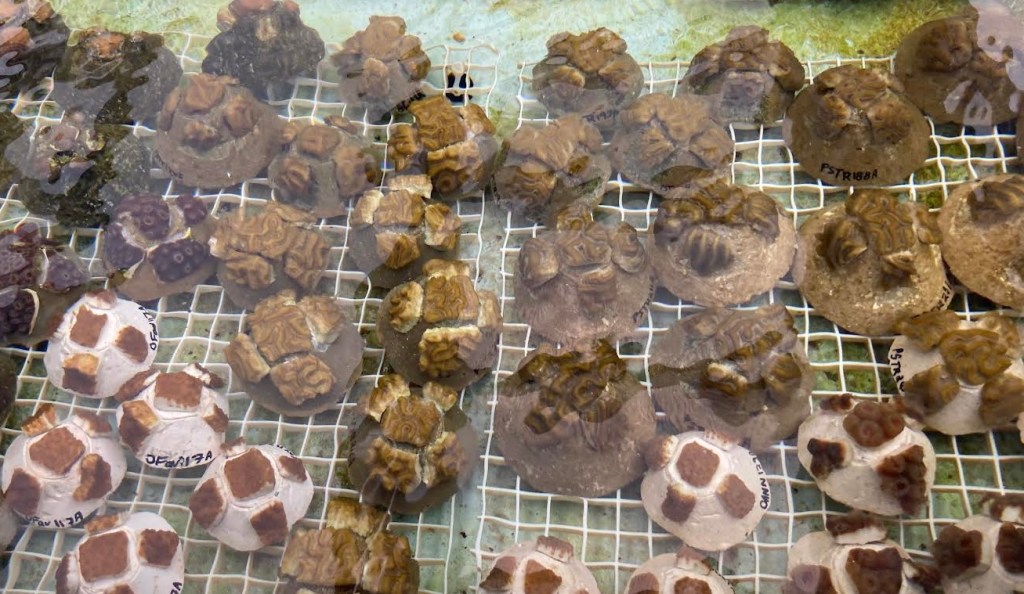

Currently, researchers like Phillips are cloning corals they retrieve from the sea giving them space and time to grow and then transplanting them back into the ocean. It’s a time consuming and arduous task, one that often results in the little creatures dying off again. And still, they try.

“I know, like parents, we’re not supposed to pick favorites,” Phillips said with a smile. “But …” She nodded at a tank that held a different type of coral babies. “These are not clones.”

The tiny corals in question were bred from sperm and eggs that are released once a year by the millions, a synchronized dance which often occurs in conjunction with a full moon. They are then gently gathered up by divers and moved to the lab tanks for fertilization.

“They provide diversification,” Phillips explained.

And that’s important, because diversity will help the corals be more resilient and better able to stave off disease. There’s also hope that corals might be developed that can thrive in the warming waters of our world’s oceans.

The effort to regrow coral can be disheartening. At one St. Croix underwater site where researchers spent three years establishing a coral nursery, 67% of the babies were wiped out in a matter of weeks, which prompted me to ask, what’s the point?

“Coral’s have been around for a very long time. Bleaching is recent,” Phillips said. “But people worldwide are studying this modern problem looking for solutions.” She gazed again at the coral babies in a glimmering tank and smiled. A scientist with hope.

Here’s hoping we find a lot more like her.

Your Forgotten Sons

Inspired by a true story

Anne Montgomery

Bud Richardville is inducted into the Army as the United States prepares for the invasion of Europe in 1943. A chance comment has Bud assigned to a Graves Registration Company, where his unit is tasked with locating, identifying, and burying the dead. Bud ships out, leaving behind his new wife, Lorraine, a mysterious woman who has stolen his heart but whose secretive nature and shadowy past leave many unanswered questions. When Bud and his men hit the beach at Normandy, they are immediately thrust into the horrors of what working in a graves unit entails. Bud is beaten down by the gruesome demands of his job and losses in his personal life, but then he meets Eva, an optimistic soul who despite the war can see a positive future. Will Eva’s love be enough to save him?

Amazon

Bookstores, libraries, and other booksellers can order copies directly from the Ingram Catalog.

Anne Montgomery’s novels can be found wherever books are sold.