As often happens this time of year, we are called upon to consider that for which we are thankful. And while I am of course grateful for family and friends and a roof over my head and food in the fridge, I’ve been leaning toward adding to that list, and it’s something that might come as a surprise.

Curiosity.

When I was a teacher, part of my job was helping teenagers prepare for the future. “What do you like to do?” I’d ask, hoping to steer them toward planning for a profession they might enjoy. But way too frequently, the answer would be, “Nothing.”

“How about sports?” I’d press. “Or hobbies?”

“Sleeping.”

I would try not to roll my eyes.

“Shopping!” many girls would pipe up.

These conversations routinely frustrated me, because I liked to do so many things. In fact, I still do. Which got me wondering why I run out of fingers when counting up subjects I find fascinating and why many of my students did not.

Turns out the answer is curiosity, something all humans are said to have in varying degrees. According to a Columbia University/Zuckerman Institute study, “At its core, curiosity evolved as a survival mechanism. It encourages living things to explore their environment, learn what is safe, and find resources.”

Consider ancient hunter-gatherers who came across an unfamiliar plant. I’m sure the puzzled about whether it was eatable, good for healing, or useful in construction of some kind. And so the experimentation began. Thanks to curiosity, they might have located something that could potentially enhance their survival.

Jacqueline Gottlieb, a PhD and lead investigator of the study, explained that humans can be curious even without the possibility of obvious rewards. “Curiosity entails a sort of enthusiasm, a willingness to expend energy and investigate your surroundings. And it’s intrinsically motivated, meaning that nobody is paying you to be curious; you are curious merely based on the hope that something good will come when you learn.”

Which had me wondering again why some of us seem to be innately curious and others are not. It turns out that curiosity is a skill, one we can learn and improve upon. But how do we do that?

This is where parents and teachers come in. We can encourage young people to develop curiosity in numerous ways. We can model curiosity by wondering aloud. “Wow! That shooting star was beautiful! Where do you think it came from?” or “Why do you think ancient people built those pyramids?”

We can take children to museums and libraries, parks and natural habitats, and let them explore, noting what they might be instinctively drawn to, subjects we can build on. For example, I’ve been a rock collector since I was in elementary school—I have about 400 specimens in my living room alone— a hobby that often prompts the question, “Why?” I finally realized it was those trips to the Museum of Natural History in New York where I was fascinated by the gem and mineral collection, and the camping trips where I’d find rocks strewn in forests and streams. Note that when I was 12, my parents gave me a geology science kit for Christmas, containing, among other things, a book with colorful pictures of rocks, a tiny hammer, and a collection of mineral samples. I was charmed. Perhaps today I would not be a rock collector, a hobby that gives me immense joy, had my parents not exposed me to them at such an early age.

I realize in today’s frantic world some parents just don’t have the time to explore with their children, so supporting such efforts at school could be the answer. Those field trips you might recall from your youth were learning experiences chosen to broaden your horizons, events to prompt questions, and, yes, boost curiosity.

And while we must do our best to instill a sense of curiosity in the generations that follow, we shouldn’t forget ourselves. I’ve learned that, as we age, we are often no longer able to do some of the things we love, which is why it’s so important to be curious. We should never stop looking into new subjects and hobbies. Nor should we forget that “Why?” is a beautiful gift, one for which we should all be thankful.

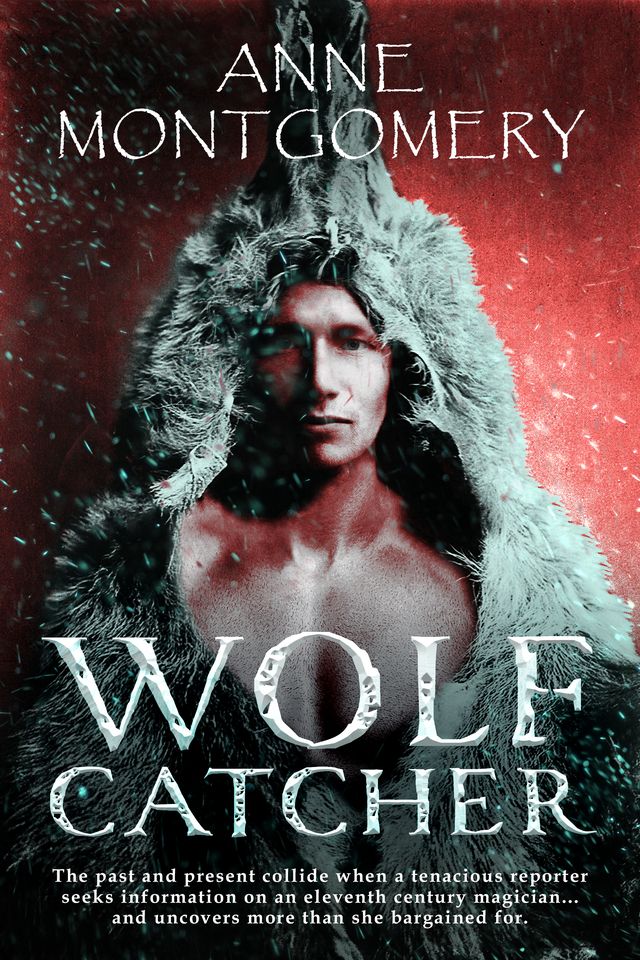

Wolf Catcher

Anne Montgomery

Historical Fiction

In 1939, archeologists uncovered a tomb at the Northern Arizona site called Ridge Ruin. The man, bedecked in fine turquoise jewelry and intricate bead work, was surrounded by wooden swords with handles carved into animal hooves and human hands. The Hopi workers stepped back from the grave, knowing what the Moochiwimi sticks meant. This man, buried nine hundred years earlier, was a magician.

Former television journalist Kate Butler hangs on to her investigative reporting career by writing freelance magazine articles. Her research on The Magician shows he bore some European facial characteristics and physical qualities that made him different from the people who buried him. Her quest to discover The Magician’s origin carries her back to a time when the high desert world was shattered by the birth of a volcano and into the present-day dangers of archeological looting where black market sales of antiquities can lead to murder.

Bookstores, libraries, and other booksellers can order copies directly from the Ingram Catalog.

Anne Montgomery’s novels can be found wherever books are sold.